The following blog post features student writing.

Hello, everyone! The fifth day of our journey involved learning about some fascinating Chinese engineering and hiking up and down one of China’s most famous Daoist mountains.

The first thing we did was visit the Dujianyan, the ancient irrigation system that gives Dujianyan City its name. The system was created during the Qin Dynasty in 256 BC to help farmers. It runs on the Minjiang, the longest tributary of the Yangtze. Initially, the Minjiang came down from the Min mountains, making nearby farmlands vulnerable to flooding. In order to harness the power of the river, Li Bing—the governor of Shu during the Qin Dynasty—developed a method of channeling and dividing the water rather than simply creating a dam.

We walked around the Dujiangyan, exploring the three main constructions that work together for maximum efficiency. These constructions are the Yuzui, the Feishayan, and the Baopingkou. The Yuzui is an artificial levee that divides the water into inner and outer streams. The inner stream is deep and narrow so that it carries around 60% of the river’s flow into irrigation systems during the dry seasons. The Feishayan is an opening that connects the two streams for protection against flooding. It allows the natural swirling of the water to drain out excess water from the inner stream into the outer stream. The Baopinkou distributes the water from the system into the farmlands of the Chengdu plain through the mountain.

We ended our exploring at the Yuzui (we started backwards) and had a lot of time to look around—a grand total of 10 minutes. Still, in that time, we were able to take some fine pictures and buy a couple of fresh cucumbers, which were surprisingly refreshing.

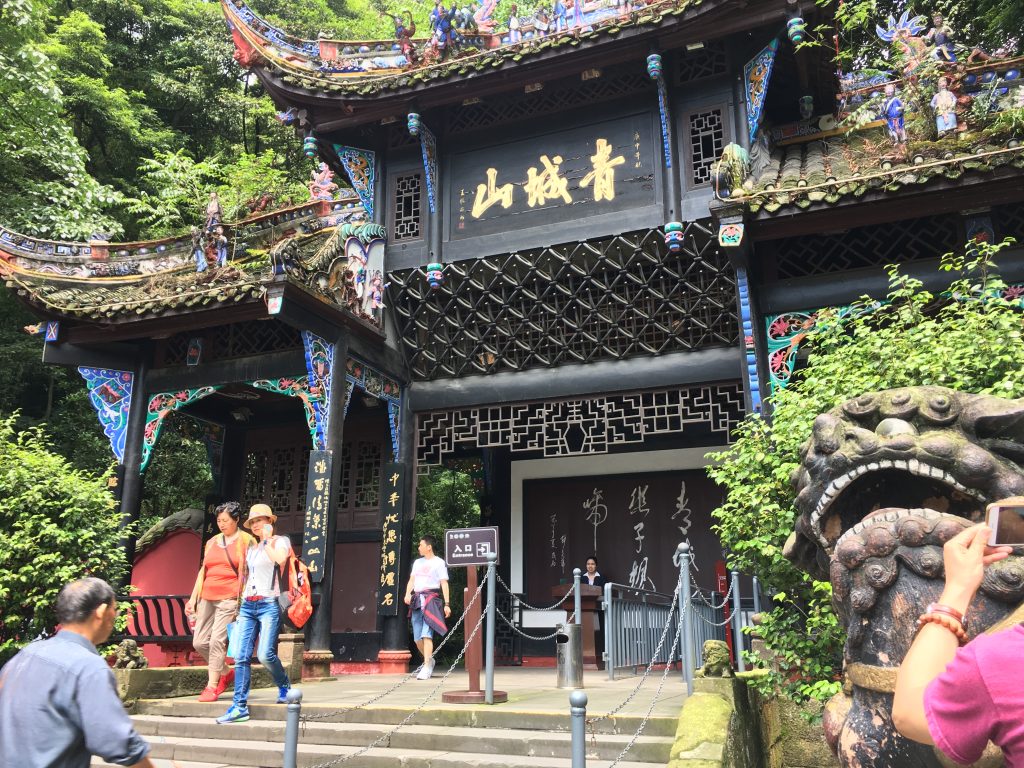

Afterward, we took a quick bus ride to the entrance of Qingcheng Mountain (青城山), one of China’s most important Daoist centers. Daoism, also known as Taoism, is a religious or philosophical tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Dao (道, literally “Way”). Although the Dao is a fundamental idea in most Chinese schools of philosophy, in Daoism, it denotes the principle that is simultaneously the source, pattern, and substance of everything that exists. While Daoist ethics vary depending on the particular school, all forms of Daoism tend to emphasize wu wei (无为 — no unnatural action), naturalness, simplicity, spontaneity, and the Three Treasures: ci (慈 — “compassion”), jian (俭 — “moderation”), and bugan wei tianxia xian (不敢为天下先 — literally “not daring to act as first under the heavens,” but usually translated as “humility”).

Entrance to Qingcheng Mountain.

To get to the top of the mountain, we did a combination of walking, taking shuttle cars, and riding a cable car. Along the way, we saw many smaller shrines and temples dedicated to various Daoist figures, particularly Lao Zi, an ancient philosopher and the founder of Daoism.

One of the shrines we found.

There were also people selling various snacks and drinks (we found ice cream on the way down!), and one particular item that caught our attention was cucumber; people would peel off the skin and just eat a whole cucumber. It was surprisingly very refreshing and tasty.

The cucumbers

For the way down, we chose to walk the entire distance—well over an hour of hiking. The scenery was absolutely gorgeous the entire way, and the long walk gave us plenty of time to talk with each other.

We were all exhausted when we returned to the hotel, so we ended the day with a delicious skewer dinner and desserts from a bakery near our hotel.

Skewer dinner.

Tomorrow (June 10), we head to Chongqing and board a cruise!

Take care, and thanks for reading.

– Jungwoo & Ryan